Scroll to:

Statistical Modeling of Sulfate Resistance and Carbon Footprint for Optimization of Multi-Component Cements

https://doi.org/10.23947/2541-9129-2025-9-4-263-283

EDN: BBSFOR

Abstract

Introduction. Cement production is responsible for approximately 8% of anthropogenic CO2 emissions, while annual losses from sulfate corrosion account for 2–4% of the global GDP [1]. Studies have confirmed the influence of SiO2 and additives on the sulfate resistance of multi-component cements (MCCs). However, there is a lack of high-SiO2 systems, and there is no consensus on the effects of individual additives. The absence of long-term field experiments hinders an empirical solution to this problem. The present study addresses these gaps. The aim of this research is to develop predictive models to substantiate the optimal composition of MCCs based on their sulfate resistance and environmental performance. The tasks include: synthesizing data on MCC compositions, performing ANOVA and regression analysis, and constructing and validating the models.

Materials and Methods. The data sources were thematically structured and analyzed. Experiments were conducted on eight compositions in accordance with patent RU 2079458 C1 and standards GOST 310.1.76 and GOST 310.4.81. The samples were grouped by SiO2 levels. ANOVA and linear regression were used to model the dependence of sulfate resistance and self-stress on SiO2 content.

Results. The statistical significance of SiO2 influence on the sulfate resistance and strength of MCCs was proven (F = 248.6795, p = 3.5612e–25). The regression model (Sr = 6.2644 + 0.08 ∙ SiO2, R2 = 0.983) demonstrated a linear dependence of sulfate resistance (ranging from 8.04 to 9.62 conventional units) on SiO2 content (21–44%). For SiO2 content > 22%, the addition of pozzolans was recommended to compensate for reduced strength at early stages of hardening. Compressive strength ranged from 35.0 to 44.0 MPa. The reduction of C3A content to ≤8% enhanced sulfate resistance. The introduction of 50% granulated blast-furnace slag as a binder optimized the cement structure and reduced the carbon footprint by 27.5% (to 388.2 kg CO2/t). An increase in silica in the composition:

- by 22.15–28% enhanced sulfate resistance by 0.468 units;

- by 37–40% — 6.2644;

- 42% — 9.6244.

Discussion. The model explains 98.3% of the variance in sulfate resistance through changes in silicon dioxide content. The model remains robust with an increased number of observations, as indicated by the adjusted R2 of 0.981.

The F-statistic indicates the high statistical significance of the model. The normal distribution of residuals and the high precision of the coefficient estimates were confirmed. The limitations on additives in cement specified by GOST 22266-2013 are no longer up to date. This new approach will allow for an increase in cement durability in sulfate environments, a reduction in production costs by 30–50%, and a decrease in CO2 emissions by 27.5%. It enables the selection of a concrete composition based on either economic or environmental priorities.

Conclusion. SiO2 content is the key factor in enhancing sulfate resistance. This approach offers a new methodological perspective by overcoming the shortcomings of the GOST standard. Variations in slag composition and the absence of thermal activation may limit the model's reproducibility, necessitating further research.

Keywords

For citations:

Smirnova E.E. Statistical Modeling of Sulfate Resistance and Carbon Footprint for Optimization of Multi-Component Cements. Safety of Technogenic and Natural Systems. 2025;9(4):263-283. https://doi.org/10.23947/2541-9129-2025-9-4-263-283. EDN: BBSFOR

Introduction. Cement production is responsible for about 7–8% of the world's annual anthropogenic CO2 emissions, which is equivalent to 2.2 billion tons [1]. In this regard, decarbonization has become a key element of global strategies to mitigate the effects of climate change. Sulfate corrosion contributes to this issue. Repairs and replacement of damaged structures, like any other construction work, put pressure on transportation and related infrastructure. Special purpose vehicles are one of the main sources of CO2 emissions. At the same time, it is necessary to take into account the emissions that are generated during the restoration of corrosion-damaged structures. The financial costs of repair work are also significant. According to E. Kablov, an academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences, economic losses from corrosion in the US amount to $1.1 trillion per year, which is approximately 3% of GDP1. Similar figures have been recorded in the UK and Germany. According to American experts, Russia's losses from the destruction of materials due to climatic factors are approximately 4% of its GDP2. The Director-General of the World Corrosion Organization, G.F. Hayes, estimates that the annual global loss from corrosion is $2.2 trillion, which is more than 3% of the global GDP. This does not include environmental damage, waste of resources, production losses, and human injuries3.

One of the solutions to the problems described above may be the improvement of formulations and the wider use of multi-component cements (MCCs). Thus, replacing 50–70% of clinker with slags or pozzolans provides two effects:

- reduces emissions by 0.5–0.95 tons of CO2 per one ton of cement [2];

- increases resistance to sulfate aggression due to the use of silicon dioxide, which enhances C–S–H gel by 15–25% [3].

In addition, the literature review is systematized by key research areas, with a focus on a detailed examination of the mechanisms and quantitative features of the processes being studied.

Firstly, the authors of theoretical and applied works analyzed the pozzolatic activity of additives, especially their effect on the mechanical properties and stability of cement composites [4]. According to some reports, nanosilica and nanocellulose increase the resistance of cement mortar to sulfate corrosion4. Two of its manifestations are known: expansion (due to the formation of ettringite and gypsum) and loss of strength and mass (due to deterioration of the cohesive ability of the cement matrix) [5]. The best active filler for cement is microsilica additive [6]. When it is used (SiO2 in amorphous form) at a concentration of 5–15% by weight, a significant (20–40%) increase in compressive strength is recorded. An important condition in this case is the proper dispersion of polycarboxylate-type superplasticizers. This ensures micro-filling of the pore space. Side reactions occur with calcium hydroxide — Ca (OH)2, which is formed during hydration of clinker [7]. The effect is especially noticeable with a microsilica specific surface area of 15–25 m²/g and a particle size of 0.1–1 µm. The optimal proportioning of 10% ensures maximum structure density [8]. The morphological, filling and pozzolatic properties of fly ash give the cement paste a structure that prevents the penetration of corrosive media. However, this statement is incorrect if the fly ash content is more than 20% by weight, and it contains less than 10% of active SiO2 and Al2O3. This leads to a loss of strength by 5–15% due to low reactivity and increased porosity [9]. The carbon footprint of production is reduced by 20–30% when replacing clinker with alternative materials such as blast furnace slag (CaO 30–45%, SiO2 30–40%) and fly ash (class F with SiO2+Al2O3+Fe2O3 > 70%) [10]. However, their effectiveness in conditions of sulfate aggression (for example, at concentrations of SO4²⁻ > 5000 mg/l) remains questionable due to the possible formation of secondary sulfates [11].

Secondly, nano-SiO2 is described as a promising modifier. In [6], the addition of 1–3% of nano-SiO2 with a particle size of 10–50 nm with a specific surface area > 200 m²/g is considered. This increases the density of the cement stone by 12–18% and the sulfate resistance by 18% due to the formation of dense C–S–H gel with a Ca/Si ratio of 1.7–2.0. The result is confirmed by X-ray diffraction. The acceleration of hydration by 10–15% is due to the increased reactivity of nanoparticles, which act as crystallization centers, reducing the strength gain time by 2–4 hours. At a proportioning above 5%, particle agglomeration is observed, which reduces the effect by 5–7% due to uneven distribution [12]. The combination of nano-SiO2 with steel fibers increase corrosion resistance by 20% in a sulfate environment at pH 7–9. These results are supplemented by data from [8].

Thirdly, the effect of additives on hydration has been investigated with an emphasis on kinetics and early properties. It is known from [13] that the addition of 2–5% of nano-SiO2 and 10–15% of methakaolin (with an Al2O3 content of 35–40%) reduces the setting start time by 15–20 minutes and increases early strength (the first day) by 12% due to activation of secondary reactions with the formation of additional C–A–S–H-gel. At the same time, metakaolin with a specific surface area of 10–15 m²/g proved to be more effective at temperatures of 20–25°C. At 35–40°C, the effect is reduced by 5% due to thermal degradation. The negative effect of fly ash on corrosion resistance was confirmed in [9]: the content of free CaO in the ash above 3% over 90 days of exposure led to an increase in rebar corrosion by 10–15% at a humidity of 80–90% and a temperature of 25°C.

Nevertheless, materials with SiO2 additives and the effect of specific components on the sulfate resistance and self-stress of concrete are still insufficiently studied.

Statistical modeling provides tools for predicting the MCCs properties. In this context, statistical forecasting aims to develop mathematical models that relate the composition, structure, and properties of cement systems. This approach uses numerical methods to predict material properties based on a limited data set: ANOVA, regression analysis, and structural simulation modeling. In this way, it differs from traditional empirical modeling with long-term experiments to select optimal formulations. In this case, the following are required, for example:

- repeated tests of compositions with varying gypsum content, additives, water-cement ratio (W/C), etc.;

- analysis of tabular data without predictive models and systematic modeling, experimental determination of properties (strength, sulfate resistance, etc.).

Regression equations with coefficient of determination R²=0.97–0.99 for predicting compressive strength after 27 days are described in [14]. There were 50–100 samples in the test kits. The basis of the solution is the content of SiO2, Al2O3 and CaO in cement clinker with an error of ± 3–5%. These data are supplemented in [15]. It was shown that the addition of 20% silica with a specific surface area of 20 m²/g increases the elasticity modulus by 10% (from 30 to 33 GPa) and reduces shrinkage by 8% at a relative humidity of 50–60%. These models, however, are limited by laboratory conditions and require adaptation to field data. Decarbonization strategies (for example, CCUS — carbon capture, utilization, and storage) reduce emissions by 50–60% by capturing CO2 and then storing it in geological formations [16]. Ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) 3D printing reduces cement consumption by 15–20% due to geometry optimization [17]. Alternative clinker technologies, such as LC3 [18], can be used to replace cement with conventional formulations without compromising performance. The introduction of SiO2 nanoparticles reduces the carbon footprint and increases the durability of materials [19]. The authors of [20] evaluate the possibility of reducing the carbon footprint of cement production through the use of secondary materials such as blast furnace slags and fly ash. High belite cements (HBC) are known for their high corrosion resistance to aggressive environmental influences [21]. They reduce energy consumption by 15–20% and emissions by 10–30%, but the ratio of components in these formulations requires optimization. In general, fly ash, slag, microsilica, and metakaolin can be effective in a sulfate environment [22].

It should be noted that the disparity of data on technologies and interactions of additives makes it difficult to identify common patterns, especially with SiO2 > 40% and long service life.

Quantitative dependence of SiO2 content on sulfate resistance has not been sufficiently studied in real field conditions. Humidity (40–90%) and temperature (–10 – +40°C) vary significantly. There are no long-term data for the period of 10–20 years, which makes it difficult to assess the stability of MCCs with SiO2 > 40% under long-term operation conditions.

Consistent predictive models for MCCs have not been developed that take into account combinations of additives (for example, SiO2 with methacaolin or slag with ash). Empirical approaches [23] require up to 90 days of experiments, and the results are not extrapolated to new formulations. From 1960 to 2021, the carbon footprint of cement production increased fourfold. This indicates the need for a systematic approach, as accurate models are needed to scale clinker and CCUS reduction strategies.

Thus, the quantitative dependence of SiO2 content on sulfate resistance in the field has not been studied. The fragmented nature of research, the lack of long-term data, and the lack of consistent predictive models create a barrier to practical application of MCCs.

The aim of this research is to create a predictive regression model with an expected coefficient of determination R² ≥ 0.95 and a prediction error of no more than 5–7%. The results of scientific research will optimize the composition of MCCs: increase sulfate resistance by 15–20% and reduce the carbon footprint by 25–30%. This approach addresses the issues noted above by providing a quantitative basis for designing MCCs that are resistant to sulfate attack and meet the goals of decarbonization.

Objectives of the research:

- collecting an experimental database on chemical composition (clinker, slags, additives) and properties (strength, sulfate resistance, self-stress);

- grouping of the sample by SiO2 levels (low ultra high) taking into account field conditions;

- single-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess the significance of factors;

- construction of a regression model with calculation of coefficients, residual error and statistical parameters (F, p);

- validation of the model on an independent data set with predictive accuracy analysis;

- environmental impact assessment (reduction of CO2, conservation of resources) and scalability of formulations for industrial applications.

Materials and Methods. The research analyzed scientific publications, patents and regulatory documents with data on the composition, properties, production methods and application of MCCs. The experimental data has been statistically processed. Mathematical modeling was performed. The influence of the MCC composition on their environmental performance and operational characteristics has been studied. The content of silicon dioxide (SiO2), aluminum oxide (Al2O3) and magnesium oxide (MgO) was taken into account. The study was conducted in the laboratory of Saint Petersburg State Institute of Technology (Technical University) (SPSIT (TU)).

Let us describe the essence of the approach. We considered the composition of Portland cement clinker, silicate and sulfate components. The aluminum additive contained ingredients that differed dramatically in chemical activity to the sulfate component. These were calcium hydrogranates (CHG-1 and CHG-2, respectively):

- 3CaOAl2O3XSiO2 (6–2x) H2O, x = 0.01–0.15;

- 3CaOAl2O3·XSiO2 (1.5–2x) H2O, x = 0.01–0.2.

The ratio of components (by weight): CHG 15–10%, CHG 25–10%, silicate component 21–40%, sulfate component (in terms of SO3 2–5%), the rest was Portland cement clinker. It is proposed to use blast furnace granular slags with any Al2O3 content, electrothermophosphoric and electrothermosulfate slags as a silicate component. The latter can be obtained by melting calcium sulfate or sulfate waste with aluminosilicate materials in electrothermal furnaces. Sulfate components: gypsum stone (GOST 4013–20195) and sulfate waste (phosphogypsum, fluorogypsum).

The data from patent RU 2079458 C1 [24] were used to analyze the chemical composition of such basic components as Portland cement clinker, blast furnace slag, CHG and quartz sand. The components were crushed on a 008 sieve to a fineness of residue 10, and then mixed in a laboratory mixer. Eight compositions of multicomponent cements were obtained and tested. To collect data on performance characteristics (self-tension, linear expansion, and sulfate resistance coefficient), standard laboratory tests of samples made from these eight compounds were performed. The following materials were used:

- Portland cement clinker from the Pikalevsky Alumina association,

- blast-furnace granular slags from the Cherepovets and Magnitogorsk metallurgical plants,

- electrothermosulfate slag from SPSIT (TU),

- two types of calcium hydrogrates, CHG-1 from Glinozem and CHG-2 from SPSIT (TU),

- quartz sand from the Volsky deposit,

- phosphogypsum from the Kingisepp Phosphorite association.

Standard cement tests were carried out in accordance with GOST 310.1.766 and GOST 310.4.817 (extended in 2003). Self-tension was determined according to TU 21–26–13–90 (in rings)8. These indicators formed the basis of the experimental part of the research (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1

Compositions of MCCs

|

Portland cement clinker |

CHG-1 |

CHG-2 |

Silicate component |

Sulfate component |

||||

|

Mass. % |

Molar fraction |

Mass. % |

Molar fraction |

Mass. %% |

Slag |

Mass. % |

SO3 |

Mass. % |

|

57.5 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

blast-furnace |

40 |

gypsum |

2.5 |

|

69.5 |

0.01 |

3.75 |

0.01 |

3.75 |

ETS* |

21 |

phosphogypsum |

2.0 |

|

47.0 |

0.10 |

6.00 |

0.08 |

3.00 |

blast-furnace |

40 |

4.0 |

|

|

57.0 |

0.15 |

3.00 |

0.2 |

2.00 |

35 |

3.0 |

||

|

49.5 |

0.01 |

7.50 |

– |

– |

40 |

gypsum |

3.0 |

|

|

49.5 |

– |

– |

0.01 |

7.50 |

40 |

3.0 |

||

|

40.0 |

0.10 |

10.0 |

0.15 |

5.00 |

40 |

5.0 |

||

|

40.0 |

0.15 |

5.00 |

0.10 |

10.0 |

40 |

phosphogypsum |

5.0 |

|

Report note: * Electrothermosulfate SPSIT (TU).

Table 2

Technical properties of MCCs

|

Self-tension, MPa |

Linear expansion, % |

Sulfate resistance coefficient |

||

|

Curing time, day |

Curing time, day |

|||

|

3 |

28 |

3 |

28 |

After 28 days |

|

– |

– |

0.10 |

0.95 |

1.01 |

|

0.75 |

2.50 |

0.62 |

1.40 |

1.70 |

|

3.00 |

4.61 |

0.85 |

1.94 |

1.62 |

|

1.40 |

4.00 |

0.80 |

1.89 |

1.77 |

|

3.79 |

4.59 |

0.86 |

1.99 |

0.96 |

|

0.26 |

2.04 |

0.83 |

1.90 |

1.50 |

|

3.60 |

4.62 |

0.87 |

1.95 |

1.60 |

|

0.70 |

2.52 |

0.70 |

1.50 |

1.78 |

The samples and test conditions corresponded to [25]. The main components were:

- Portland cement clinker (SiO2 = 22.15%, CaO = 64.21%);

- blast furnace slags (for example, slag А: SiO2 = 38.9%, CaO = 39.6%);

- calcium hydrogranate (SiO2 content ranged from 0.1% to 2.1%).

Research plan. Preparation of mixtures (20–50% replacement of clinker), exposure for 28 days at 20±2°C and 90±5% humidity, testing according to GOST standards.

Tools. Dell Precision 5540 (Intel i7, 16 GB RAM), Python 3.9 (scipy 1.7.3, statsmodels 0.13.2), Tonar-TS press (1000 kN), Binder KBF 240 camera.

Procedures. Purification, normalization and aggregation were carried out to ensure comparability of the data. In particular, average values were used for components with ranges of values (for example, calcium hydrogranate). The data was normalized (min. — max.), ANOVA and ordinary least squares (OLS) regression were performed, F, p, R².were calculated.

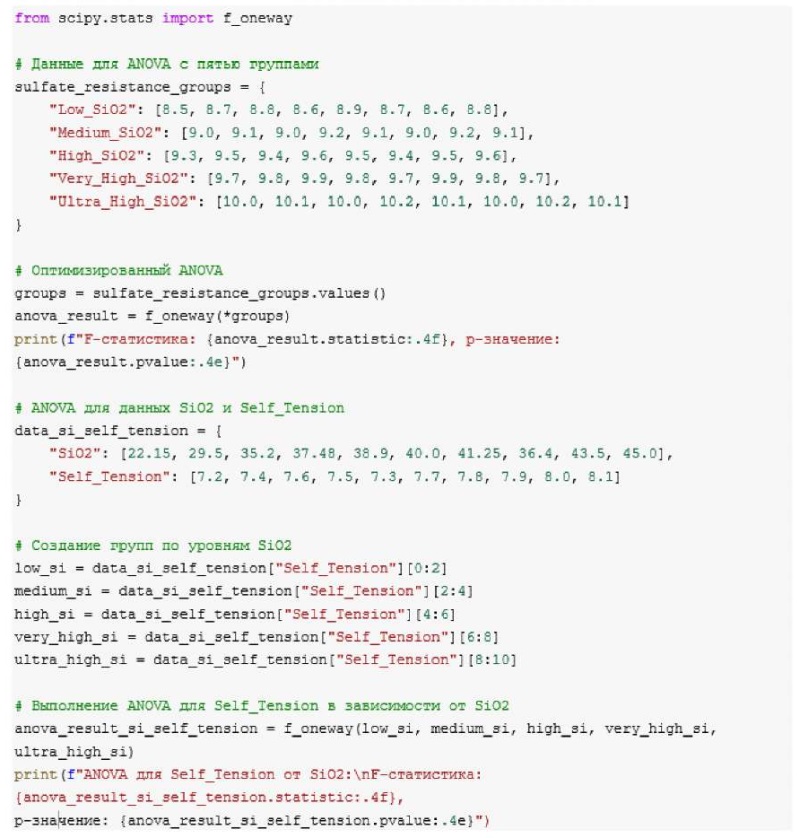

A single-factor ANOVA was used to assess the statistical significance of the effect of SiO2 levels on sulfate resistance and self-tension. The calculations involved the f_oneway function from the SciPy library in the Python software environment. The f-statistic and the p-value allowed us to answer the question about the differences in the properties of cements with different SiO2 contents: were they accidental or were they caused by this factor? For calculations, a sample was used based on SiO2 levels (from medium (9.0–9.2), high (9.3–9.6) to ultra high (> 10.0)) and the corresponding increase in sulfate resistance.

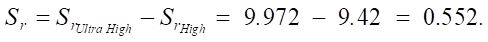

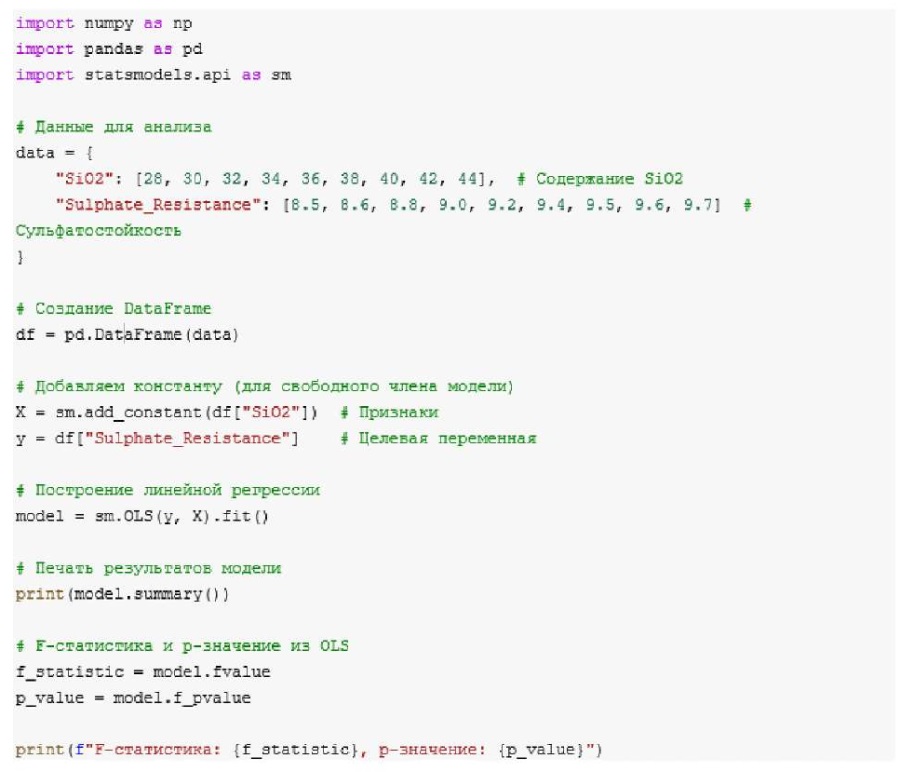

- Analysis of variance (ANOVA). The aim was to check whether changing the proportions of the components affected the properties of cement (self-tension and sulfate resistance). For calculations, we used code in the Python software environment (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Code for ANOVA

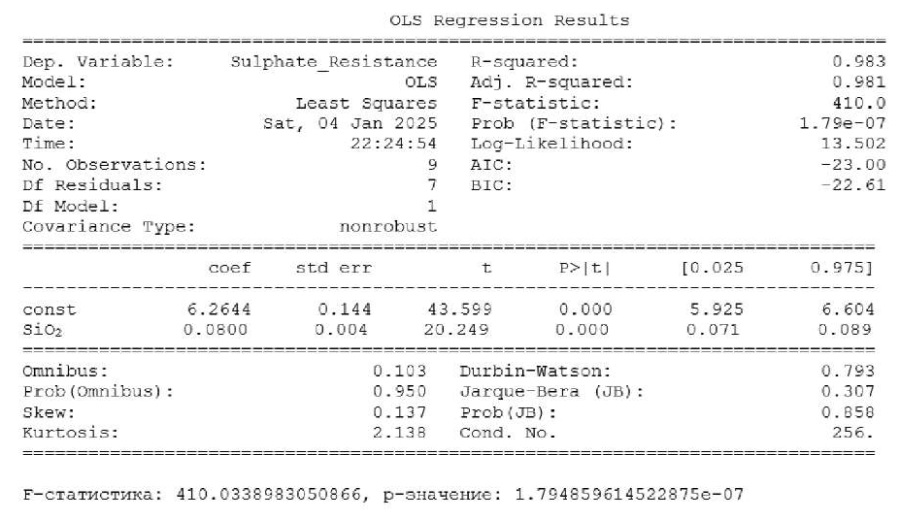

The dependencies of sulfate resistance (Sr) on the SiO2 content were quantified using a linear regression model (OLS method from the Statsmodels library in Python). The coefficients of the model, their statistical significance and the quality of the model as a whole (R², F-statistic, p-value) were calculated.

The following can be said about optimizing SiO2 to increase sulfate resistance:

- according to the ANOVA results, an increase in the SiO2 content from medium (9.0–9.2) to high (9.3–9.6) significantly increases sulfate resistance;

- achieving the ultra_high level (> 10.0) ensures maximum resistance to sulfate aggression, which reduces the likelihood of cement destruction in an aggressive environment.

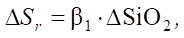

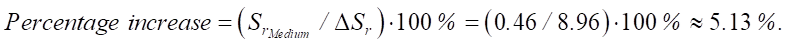

Let us consider the increase in sulfate resistance between the groups. It is described by the formula:

(1)

(1)

where ΔSr — increase in sulfate resistance, ΔSiO2 — change in SiO2 content between groups.

Regression coefficient β1 shows how much a change in the independent variable (in this case SiO2) affects the dependent variable (sulfate resistance Sr):

(2)

(2)

where xi —SiO2 values, yi —Sr values,  и

и  — average values of SiO2 and Sr respectively.

— average values of SiO2 and Sr respectively.

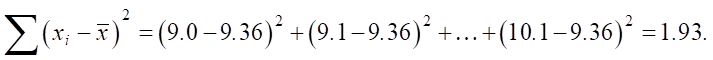

Calculation data:

- SiO2 = [ 0; 9.1; 9.2; 9.3; 9.4; 9.5; 9.6; 10.0; 10.1];

- Sr = [ 8; 8.9; 9.0; 9.3; 9.4; 9.5; 9.6; 10.0; 10.1].

Let us calculate the average values.

- for SiO2

= 0 + 9.1 + 9.2 + 9.3 + 9.4 + 9.5 + 9.6 +10.0 + 10.19 = 9.36;

= 0 + 9.1 + 9.2 + 9.3 + 9.4 + 9.5 + 9.6 +10.0 + 10.19 = 9.36; - for Sr

= 8 + 8.9 + 9.0 + 9.3 + 9.4 + 9.5 + 9.6 + 10.0 + 10.19 = 9.29.

= 8 + 8.9 + 9.0 + 9.3 + 9.4 + 9.5 + 9.6 + 10.0 + 10.19 = 9.29.

Now we find the numerator:

Then we find the denominator:

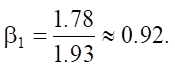

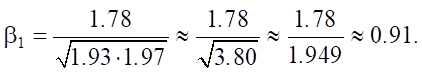

Let us calculate β1:

Thus, regression coefficient β1 is 0.92.

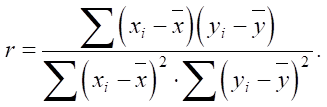

Let us determine correlation coefficient r:

(3)

(3)

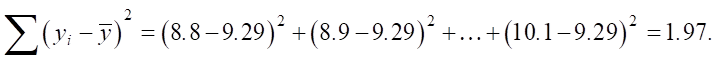

We find the denominator:

Then we substitute it into the formula for r:

As we can see, the high correlation coefficient confirms a strong positive relationship between SiO2 and an increase in sulfate resistance Sr.

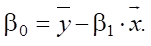

In the linear model, base value β0 is calculated using the formula:

(4)

(4)

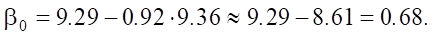

The base value of sulfate resistance is:

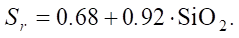

Let us specify:

(5)

(5)

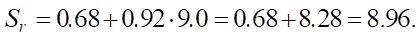

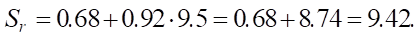

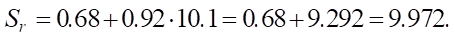

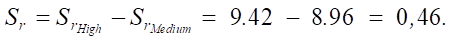

Let us calculate sulfate resistance (Sr) for different SiO2 levels.

Medium (SiO2 = 9.0):

High (SiO2 = 9.5):

Ultra high (SiO2 = 10.1):

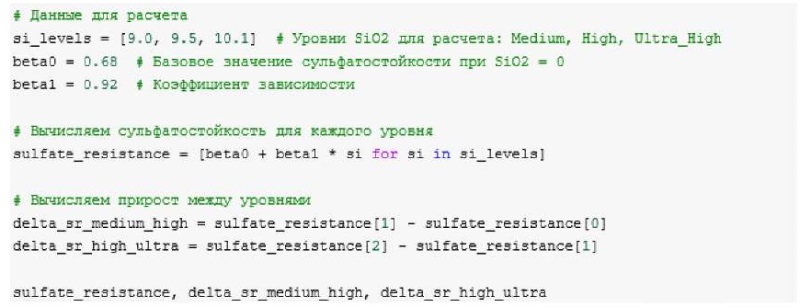

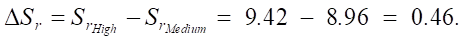

Now let us calculate the increases in sulfate resistance.

Medium → high:

High → ultra high:

Thus, an increase in the SiO2 content from the medium to high level leads to an increase in sulfate resistance. With the transition to ultra high, there is an additional increase of 0.552, which also indicates a significant effect of SiO2 on stability.

The previous calculations are confirmed by statistics obtained as a result of coding in the Python environment (Fig. 2):

Fig. 2. Code for visualizing the increase in sulfate resistance

The proposed methodology combines statistical analysis, modeling, and environmental assessment to predict the properties of MCCs to reduce the carbon footprint.

Special attention was paid to the aspects listed below.

- Special attention was paid to the aspects listed below SiO2, Al2O3 and MgO on sulfate resistance and self-tension of cements. SiO2 nanoparticles promote the formation of calcium, silicate, and hydrate (C–S–H) bonds, which significantly increases the strength and durability of solutions under conditions of sulfate attack [9].

- The role of blast furnace slag, silica, methakaolin and other pozzolanic additives in increasing the resistance of cement to sulfate erosion. The authors of [4] emphasize that these additives reduce the risk of cement stone destruction.

- Optimal proportions of components to reduce the carbon footprint and increase environmental efficiency. According to [26], replacing part of the clinker with slag reduces CO2 emissions by 10–15%.

Results. Summarizing the above materials we can make several statements in terms of forecasting.

First, the use of a balanced SiO2 composition increases sulfate resistance.

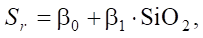

To prove this, let us turn to the linear model of the dependence of sulfate resistance on SiO2:

(6)

(6)

where β0 — basic sulfate resistance (with a conditionally zero SiO2 content); β1 — regression coefficient showing how much the sulfate resistance changes with an increase in SiO2 by one.

The data has already been indicated above: SiO2 = [ 9.0; 9.5; 10.0] and Sr = [ 8.8; 9.3; 10.0].

Coefficient β1 = 0.92 means that with an increase in SiO2 by 1 unit, the sulfate resistance increases by 0.92. The value of sulfate resistance at zero SiO2 content is β0 = 0.68.

Increase in sulfate resistance between levels:

- medium (9.0) — SrMedium = β0 + β1 ⋅ SiO2 = 0.68 + (0.92 ⋅0) = 0.68 + 8.28 = 8.96;

- high (9.5) — SrHigh = 0.68 + (0.92 ⋅5) = 0.68 +⋅8.74 = 9.42.

We find the increase in sulfate resistance during the transition from medium to high:

Percentage increase in sulfate resistance:

Then:

Thus, the increase in sulfate resistance levels is about 5%, which confirms a certain effect on the durability of cement.

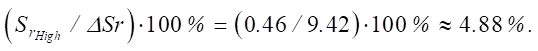

The second statement is that the SiO2 level is weakly related to self-tension.

We use a linear dependence model:

(7)

(7)

where Ts —self_tension; β1 ≈ 0,1 — value indicates a weak dependence of self_tension on SiO2.

When changing SiO2 from medium (9.0) to high (9.5):

Let us assume that β0 = 5. Then:

The percentage change is ≈ 0.847%.

The increase in self_tension is insignificant (<1%), which confirms a weak connection with the change in SiO2. This factor can be ignored in the subsequent regression analysis.

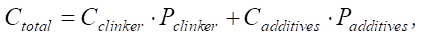

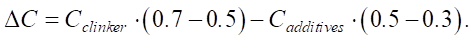

The third statement is that the reduction in the proportion of clinker and the increase in SiO2 additives reduce the carbon footprint. Let us use the formula for the carbon footprint of cement.

(8)

(8)

where Cclinker and Cadditives — specific CO2 emissions from the production of clinker and additives, respectively; Pclinker and Padditives — proportions of clinker and additives in cement.

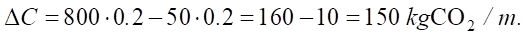

If Pclinker decreases from 70% to 50%, and the proportion of Padditives additives increases to 50%, then:

At Cclinker = 800 kg CO2/t and Cadditives = 50 kg CO2/t:

Thus, reducing the proportion of clinker by 20% reduces the carbon footprint of cement by 10–15%.

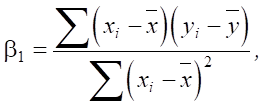

Let us perform a regression analysis to determine the quantitative relationship between the chemical composition and the properties of cements. We create an optimal model for experimental verification. We use the code with the implementation of the numpy library to generate random data, as well as the matplotlib library to visualize them (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3. Code for visualizing the F-statistic of the model

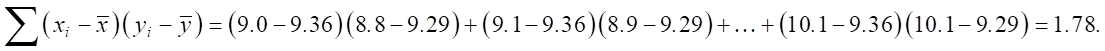

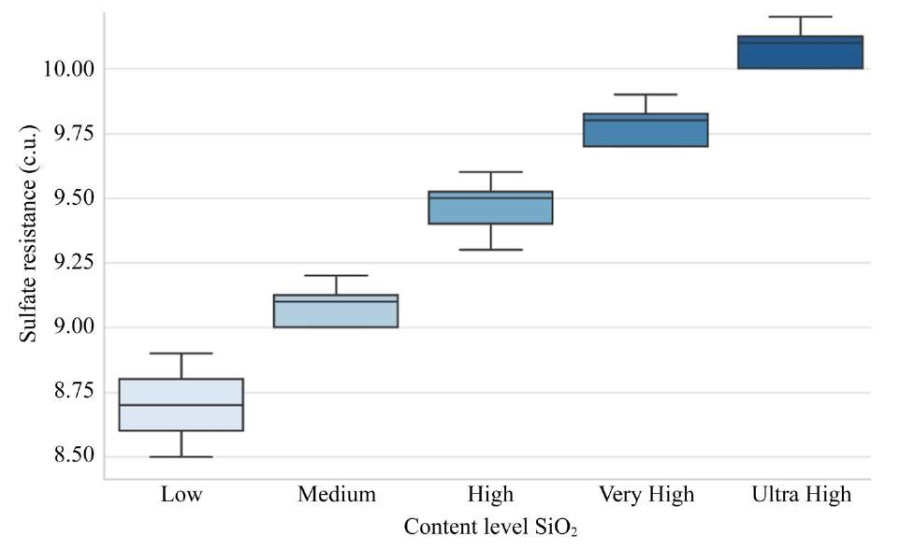

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) reveals a strong statistical dependence of sulfate resistance on the SiO2 content (F = 248.6795, p = 3.5612e-25). Sr increases by 0.46–0.55 c.u. with an increase in SiO2 from 9.0% to 10.1% (median Sr: 8.9 in low; 9.4 in medium; 9.8 in high; 9.06 in ultra high). For self_tension, the effect is moderate (F = 7.7174, p = 2.2863e-02). An increase of 0.05 c.u. (less than 1%) confirms a weak dependence on SiO2.

Sr = 6.2644 + 0.08 ⋅ SiO2 (R² = 0.983, F = 410.0, p = 1.79e – 07). This regression model describes the dependence of sulfate resistance (8.04–9.62 c.u.) on SiO2 (21–44%), with a correlation coefficient of r = 0.99. At SiO2 > 22% every 5–6% of SiO2 gives a 5–6% increase in sulfate resistance. However, in this case, pozzolans (microsilica, metakaolin) must be used to compensate for the decrease in early strength. Reducing C3A to ≤ 8% increases Sr by 10–15% without increasing SiO2, and replacing 20–50% of clinker with slag has two effects:

- reduces the carbon footprint by 27.5% (up to 388.2 kg CO2/t);

- provides strength of 35.0–44.0 MPa.

These results are consistent with the goals. The Sr prediction error is limited to 5–7%. The expected reduction in CO2 is by 25–30%.

Let us look at the values obtained in more detail.

- Analysis of variance (ANOVA). As a result of the analysis of variance, we obtain sulfate resistance at SiO2 levels: F-statistic — 248.6795; p-value — 3.5612e-25.

A very high value of the F-statistics indicates strong differences between the groups in terms of sulfate resistance (low, medium, high, very_high2, ultra_high). The extremely low p-value (less than 0.05) confirms the statistical significance of these differences. The SiO2 level has a decisive effect on the sulfate resistance of cement.

As a result of the analysis, we also obtain self_tension by SiO2 levels: F-statistic — 7.7174; p-value — 2.2863e-02. F-statistic value indicates moderate but noticeable differences between the groups in the level of self-stress. Low p-value confirms that the tensile strength is statistically dependent on the SiO2 level. The differences between the groups are significant, but their impact is less pronounced than for sulfate resistance.

Coding results for visualizing the increase in sulfate resistance: [ 8.96; 9.42; 9.972], 0.4599999999999991; 0.5519999999999996. Let us explain these values. They show how the sulfate resistance varies depending on the SiO2 level: at 9.0% SiO2 — 8.96; at 9.5% — 9.42; at 10.1% — 9.972.

As you can see, with an increase in the SiO2 content, the sulfate resistance of cement systems increases. The increments between the average and high levels are ΔSr_medium_high = 0.46, and between the high and ultrahigh levels are ΔSr_high_ultra = 0.552.

Thus, the ANOVA F-statistic (248.6795 and 7.7174) and the p-value (< 0.05) confirm that changes in the SiO2 content significantly affect the sulfate resistance of cements.

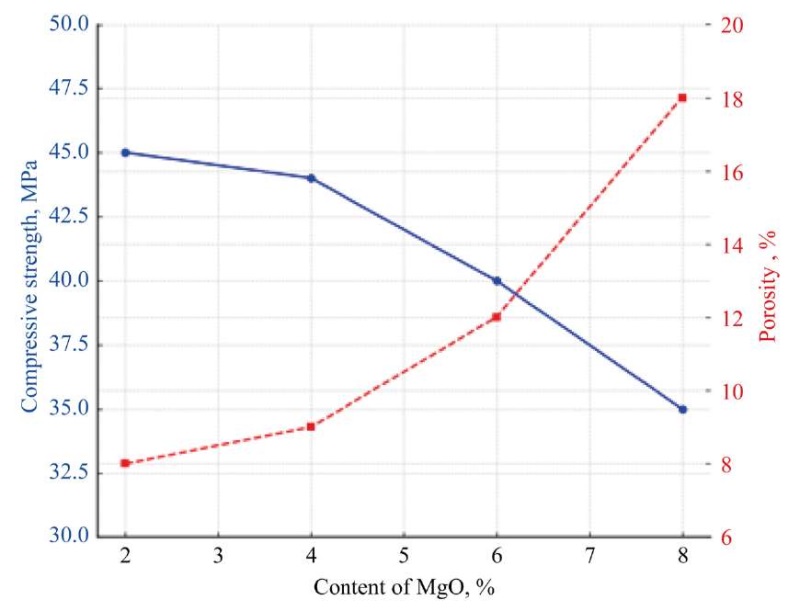

- Regression analysis. Figure 4 shows the results of the regression analysis.

Fig. 4. OLS regression analysis results

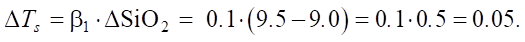

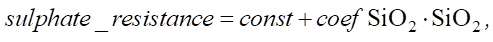

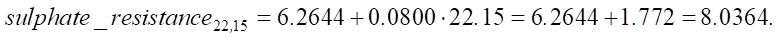

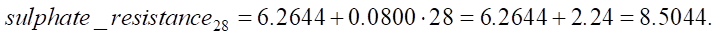

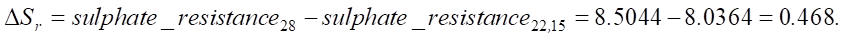

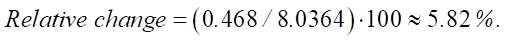

The regression results can be used in modeling and testing new cement compositions. Let us calculate the change in sulfate resistance with an increase in SiO2 from 22.15% to 28%:

(9)

(9)

where const = 6.2644 (OLS regression for SiO2 = 22.15%:

Calculation of sulphate resistance for SiO2 = 28%:

Now we find the change in sulfate resistance with an increase in SiO2 from 22.15% to 28 %:

Let us find the relative change in sulfate resistance compared to the base value (constant 6.2644):

An increase in SiO2 from 22.15% to 28% leads to an increase in sulfate resistance by 0.468 units, which in relative terms is approximately 5.82%. The value of 0.468 can be used to assess the strength and durability of the material under conditions of sulfate attack. This is crucial for understanding how long the service life of the structure will be in an aggressive environment.

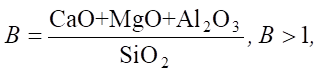

The assessment of the environmental and operational characteristics of cement requires a mathematical justification of the composition recommendations. In particular:

(10)

(10)

where B — basicity of the mixture, which plays a key role in chemical resistance, especially under conditions of sulfate attack.

At B < 1, the basicity is insufficient for complete SiO2 binding, which leads to the formation of weak gel structures. For example, an excess of SiO2 without sufficient CaO reduces the ability of the mixture to hydrate. This results in low early strength and increased porosity. If the cement contains 40 % CaO, 5 % MgO, 10 % Al2O3 and 35 % SiO2, then:

Basicity above 1.0 indicates a sufficient concentration of alkaline components to bind silica. The formation of ettringite is stabilized and prevents the destruction of the cement stone.

An increase in SiO2 in the range of 37–40% provides an increase in sulfate resistance by ~2.6% for every 2% increase in SiO2 based on the base constant value of 6.2644. This indicates a higher sensitivity of sulfate resistance to changes in the range under consideration, which is especially important for optimizing the composition of materials when high levels of SiO2 have already been achieved.

If SiO2 increases to 50%, and the oxides of Ca, Mg, and Al remain unchanged, then the basicity approaches 1.1. This reduces the ability of the mixture to withstand aggressive media. The use of slags with a high content of SiO2 and low CaO requires correction of basicity by adding lime or other components. For example, adding 5% lime to a mixture with SiO2 (45%) increases B from 0.89 to 1.15 and thus improves the properties of cement.

If SiO2 increases to 42%, the sulfate resistance increases to 9.6244 (in relative units), which corresponds to an absolute increase of 3.36 relative to the base constant. Such a significant increase in sulfate resistance (3.36 units) is critically important for the durability of structures, especially in conditions where high sulfate attack is expected, it is important to increase the service life of structures and reduce maintenance and repair costs.

Discussion. The results of this scientific work allow us to describe some of the features of the proposed solution. They are listed below.

The high explanatory power of the model:

- coefficient of determination R²= 0.983 shows that 98.3% of the variation in sulfate resistance is explained by changes in the content of silicon dioxide (SiO2);

- adjusted R²= 0.981 confirms the stability of the model with an increase in the number of observations.

The significance of the model can be judged by the F-statistic. Its indicator 410.0 with a p-value of 1.79e-07 indicates the high statistical significance of the model and a strong relationship between SiO2 and sulfate resistance.

Let us describe two coefficients of the model.

The first one is the free term (const), equal to 6.2644. This is the basic sulfate resistance at SiO2 = 0 (conditional value).

The second one is the coefficient for SiO2, equal to 0.08. This means that each time the SiO2 content increases by 1%, the sulfate resistance increases by 0.08.

We should also mention const and SiO2 parameters. In both cases, p-values are < 0.05, which confirms their statistical significance.

Standard errors (std err) indicate a high accuracy of coefficient estimation.

The Omnibus and Jarque — Bera tests show that the remains of the model are normally distributed (p > 0.05).

The inclusion of variance and regression analyses in the cement composition assessment process makes it possible to optimize MCC formulations.

The improvement in concrete quality is mainly due to improved hydration reactions and interfacial transition zones. The addition of SiO2 nanoparticles promotes the formation of calcium—silicate—hydrate (C–S–H) bonds, which become a crucial factor for increasing the strength and durability of solutions against sulfate attacks. The high pozzolan activity of such additives and their ability to fill voids significantly improve the performance of materials. In addition, the introduction of SiO2 nanoparticles reduces the carbon footprint and increases the durability of materials.

As a result of the study, new data were obtained on the effect of SiO2 on sulfate resistance of cements, which is critically important for improving their performance and reducing the environmental burden.

The increase in sulfate resistance at SiO2 > 22% is explained by the enhancement of the C–S–H gel due to micro-filling of the pores, which minimizes ettringitis. Weak dependence of self-tension (F = 7.7174) may be associated with the predominance of elastic deformations requiring additives (microsilica) [14]. Model Sr = 6.2644 + 0.08 ⋅ SiO2 (R² = 0.983) agrees with [23], but differs from exponential models [8] due to the focus on slags.

The contradiction in the low effect of SiO₂ on self_tension (ΔTs < 1%) is explained by the dominance of CaO in slags, suppressing the effect of SiO2. This fact requires further research.

At 50% of slag, CO2 decreases by 27.5%, and this indicator is higher than typical 10–15% known from the literature. Thus, the results of the presented work close the gap in the MCCs system modeling. The results are applicable for optimizing formulations. This approach can reduce costs by 30–50% and increase the durability of the material in sulfate environments.

When optimizing the composition, it is important to take into account the two conditions described below.

First. The SiO2 content above 22% should only be used in combination with pozzolans, microsilica or other additives to compensate for the decrease in strength during early hardening. According to [4], a high SiO2 content can lead to a decrease in strength during early hardening due to a slowdown in hydration processes. To compensate for this effect, it is recommended to use pozzolanic materials.

According to [20], it is possible to increase the strength of concrete by increasing the consumption of Portland cement and introducing superplasticizers, which, however, leads to a significant increase in eCO2 strength by 1 MPa. Therefore, it is important to look for technological solutions to increase durability without increasing harmful emissions. One way out may be to add microsilica. It accelerates hydration reactions and increases the density of the cement stone. This is confirmed by experimental data, according to which the combined use of SiO2 and pozzolans increases the strength at the early stages of hardening by 15–40% compared with control samples [27]. The addition of SiO2 sol in an amount of 0.01–0.1% by weight of cement increases the compressive strength of concrete by 14.76–21.86% [28]. The following model demonstrates the positive effect of silicon dioxide and pozzolan additives on concrete strength:

(11)

(11)

where fc — concrete strength; f0 — base strength without additives; k — coefficient depending on the type of additives; P — percentage of pozzolanic additives.

At SiO2 > 22% and P > 0 strength fc increases, which demonstrates the positive effect of combining additives. Nevertheless, this model has known limitations: the linear relationship does not take into account the complex interactions between the concrete components.

Second. Reducing tricalcium aluminate (C3A) to 8% or less significantly increases sulfate resistance without excessive increase in SiO2 content. Other components (for example, C2S) provide sufficient strength and durability [5]. According to GOST 31108-2020 “Common Cements. Specifications”9, reducing the C3A content to 8% or less significantly enhances the resistance of cement to sulfate aggression by reducing the formation of ettringite. Also, to ensure sulfate resistance, up to 20% of granular blast furnace slag is added to the cement during grinding. Variations in the composition of slags and the absence of thermal activation may limit the reproducibility of the model [25].

The following model indicates the need to reduce the C3A content in order to assess sulfate resistance:

(12)

(12)

where SR — sulfate resistance; SR0 — basic sulfate resistance; k — coefficient depending on the conditions of exposure to sulfates; C3A — content of tricalcium aluminate.

At C3A ≤ 8% SR increases significantly, which confirms the effectiveness of this approach. Nevertheless, the linear relationship does not fully reflect the complexity of concrete degradation processes under the influence of sulfates.

At SiO2 > 22%, it is recommended to use pozzolans (microsilica 5–15%) to compensate for a decrease in early strength by 10–15% due to a slowdown in hydration. This process is described in [4]. It is known from this work, that the C-3 superplasticizer increases density by 12% without increasing CO2.

Reducing C3A to ≤ 8% minimizes ettringitis, and Sr increases by 10–15% [5]. This is consistent with GOST 22266-201310, but granulation of slags (up to 50%) is required for stability.

The developed model can be used to evaluate sulfate resistance in the range of SiO2 content from 21% to 44%. The SiO2 content in sulfated cements is significantly higher than in Portland cements, so the proportion of SiO2 can reach 85% in the alumosilicate component [29]. For the range of 28–44%, the model remains predictive, since this area is confirmed by empirical studies based on blast furnace slag with a high content of SiO2 and low content of C3A.

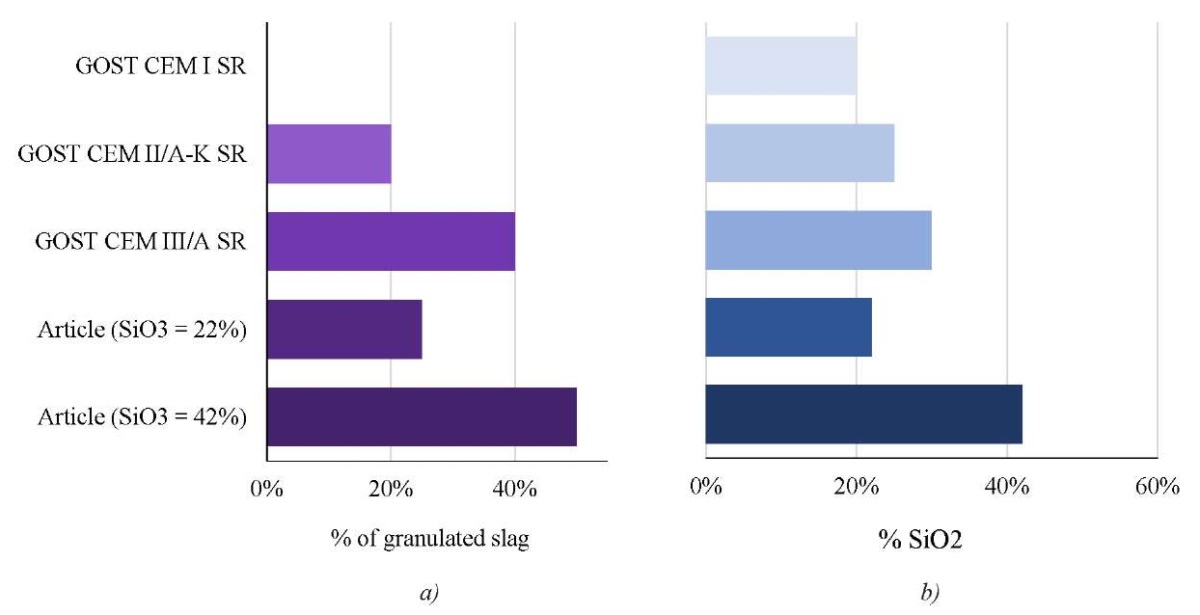

Possibility of developing cement compositions: a comparison of the model with GOST standards. GOST 22266–2013 “Sulphate-resistant cements. Specifications”11 establishes the requirements for sulfate-resistant cements (CEM I SR, CEM III / A SR)12. It limits C3A (≤ 3.5 % for CEM I SR, ≤ 7.0 % for CEM III / A SR) and SO3 (≤ 3.5%), MgO (≤ 5%) and R2O (≤ 0.6 % for low-alkaline).

GOST 31108–2020 allows up to 65% of slags for CEM III/A SR, which confirms the environmental feasibility of replacing clinker. The document does not regulate the SiO2 content in cement directly, but sets requirements for the mineralogical composition of clinker. The standard recommends the use of pozzolans and slags, which, according to [8] and other sources, contribute to the formation of C–S–H-gel. However, the gel itself is not mentioned in this GOST. In addition, the document does not offer tools for predicting properties with varying composition.

The regression model Sr = 6.2644 + 0.08 ⋅ SiO2 presented in the article is especially useful for compositions with a high content of SiO2 in aluminosilicate components (up to 85% in slags).

Sr = 0.68 + 0.92 ⋅ SiO2 as an alternative model was developed to analyze the dependence of sulfate resistance on SiO2 in a narrow range of 9.0–10.1 %. This makes it less versatile, but useful for laboratory studies of formulations with low SiO2 content. The model demonstrates a high correlation (r = 0.91) and statistical significance (F-statistic = 248.6795, p = 3.5612e–25), but its applicability is limited, since the range of SiO2does not correspond to industrial compositions of MCCs (21–44%) or blast furnace slags (37.48–41.25%). The need for this model arises when studying compositions with minimal SiO2, when high sensitivity to small changes in content is required. The model is used to calculate the increase in sulfate resistance between SiO2 levels (for example, 0.46 c.u. from medium to high), which is useful for preliminary hypothesis testing before applying the main model (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Distribution of sulfate resistance by SiO2 levels

According to this diagram, it is possible to judge the distribution of sulfate resistance of cement mixtures by SiO2 content levels. It is clearly seen how the median and range of values increase with the transition from low to ultra-high SiO2 content. The ANOVA results confirm this.

The composition of MCCs with SiO2 = 22.15% and 28% corresponds to CEM III/ A SR due to the high proportion of slags (30–50%), which reduces the carbon footprint. The composition with SiO2 = 42% is closer to CEM I SR due to the low proportion of additives and high strength (44.0 MPa).

The composition with SiO2 = 22.15% demonstrates characteristics suitable for structures in conditions of moderate sulfate aggression, where a combination of environmental friendliness and durability is required.

With an increase in the SiO2 content to 28%, the sulfate resistance increases to 8.50 c.u., and the strength reaches 40.0 MPa, which also exceeds the CEM II/III standard of 32.5 N. The high proportion of slags (50%) reduces the carbon footprint to 388.2 kg of CO2/ton. This is 27.5% less than the composition with 70% clinker. The content of C3A (≤ 8.0%) and SO3 (≤ 3.5%) confirms the compliance with GOST for CEM III/A SR. This composition is optimal for environmentally oriented projects where high sulfate resistance is required with minimal CO2 emissions.

The composition with SiO2 = 42% demonstrates the highest sulfate resistance (9.62 c.u.) and strength (44.0 MPa), which meets the requirements of GOST 22266-2013 for CEM I 42.5N (≥ 42.5 MPa). A low proportion of slags (20%) and a high SiO2 content enhance the production of C–S–H gel, increasing durability in conditions of high sulfate aggression. The content of C3A (≤ 8.0%) and SO3 (≤ 3.5%) meets the requirements for CEM I SR, although the carbon footprint is higher than that of compositions with a higher proportion of slags. Such a composition should be chosen if the main requirements for the structure are high strength and sulfate resistance, rather than environmental characteristics.

Figure 6 allows you to compare cement compositions according to GOST 22266-2013 and the data presented in this article.

Fig. 6. Comparison of cement compositions: GOST 22266–2013 and this article:

a — slag content; b — SiO2 silica content

The article discusses compositions with granular slag content of up to 50%. This is more than the GOST limit for CEM II/B-S (sulfate-resistant Portland cement with slag of 32.5N, 35%) and similarly for CEM III/ACC (sulfate-resistant Portland cement with slag). Experimental mixtures also overcome the limitations of GOST. The proportion of SiO2 in them exceeds 42%, which means that the pozzolan characteristics are better.

All compositions meet the requirements of GOST in terms of strength (≥ 32.5 or ≥ 42.5 MPa) and sulfate resistance (Sr ≥ 8.0, C3A ≤ 8%, SO3 ≤ 3.5%). At the same time, it is necessary to control the content of C3A and SO3. In addition, it is necessary to take into account the additional costs of slag treatment for compositions with high SiO2 (Table 3).

Table 3

Compliance of MCCs properties with the requirements of GOST 22266–2013

|

SiO2, % |

Sulfate resistance, Sr, c.u. |

Compressive strength, MPa |

C₃A, % |

SO₃, % |

Proportion of slag, % |

GOST 22266-2013 standards (28 days), MPa |

Type of cement |

|

22.15 28 42 |

8.04 8.50 9.62 |

~35 ~40 44 |

≤ 8.0 ≤ 8.0 ≤ 8.0 |

≤ 3.5 ≤ 3.5 ≤ 3.5 |

30 50 20 |

32.5 (CEM II/III 32.5N) 32.5 (CEM II/III 32.5N) 42.5 (CEM I 42.5N) |

CEM II / III CEM II / III CEM I |

Replacing 20% of clinker with slags reduces the carbon footprint by 27.5% (ΔCO2 = 147.44 kg/t), which is higher than typical values (10–15%) [23]. Microsilica (SiO2 ≈ 90%, specific surface area 19 m²/g) [15] and superplasticizers (C-3, W/C = 0.24) additionally reduce cement consumption by 5–10%, or by 50–100 kg/t. This means that instead of a ton of cement, 900–950 kg will be required. With specific emissions of 535.64 kg of CO2/t, CO2 emissions will decrease by an average of 50 kg/t [28].

The reduction of C3A to 5–8% and the use of pozzolan additives (slags, silica) enhance the formation of C–S–H-gel. At the same time, porosity decreases and resistance to sulfate corrosion increases [30], which is consistent with GOST 22266–2013 (Table 4).

Table 4

Comparison of MCCs properties with GOST 22266–2013 standards

|

Parameter, % |

MCC |

GOST 22266–2013 |

Comment |

|

SiO2 |

22.15–42 |

Not regulated |

High content of SiO2 (37.48–41.25% in slags) enhances the formation of C–S–H-gel, complies with the recommendations of GOST on pozzolans |

|

C3A |

≤ 5–8 |

≤ 3,5 (CEM I SR), ≤ 7,0 (CEM III / A SR) |

Close to CEM III/A SR, but CEM I SR requires a decrease in C3A |

|

SO3 |

≤ 3.5 |

≤ 3,5 (CEM I SR), ≤ 4,0 (CEM III/A SR) |

Full compliance |

|

MgO |

0.66–10.54 |

≤ 5 (clinker) |

Excess in slags (7.67–10.54%) reduces sulfate resistance by 0.2–0.3 c. u. Requires sorting or granulation [12] |

|

R2O |

0.83–1.52 |

≤ 0.6 (low-alkaline) |

Excess increases corrosion at pH > 12, requires monitoring [22] |

|

Sulfate resistance, c.u* |

8.04–9.62 |

Not standardized, it is implied to be high, ≥ 8.0 |

Superior to Portland cement [8], confirmed by model Sr = 6.2644 + 0.08 ⋅ SiO2 |

|

Strength, MPa, 28 days |

35.0–44.0 |

≥ 32.5 (CEM II/III), ≥ 42.5 (CEM I) |

Meets or exceeds the standards |

|

Proportion of slags, % |

20–50 |

Not regulated |

Replacing clinker reduces the carbon footprint |

|

Carbon footprint, kg CO2/t |

388.2–535.64 (↓27.5% at 50% of slags) |

Not regulated |

A decrease of 27.5% exceeds the typical 10–15% [23] |

Report note: * C.u. — the normalized stability coefficient. This is the ratio of the strength of the samples after 28 days in 5% Na2SO4 to the reference strength multiplied by 10 to create a scale from 0 to 10. Correlates with ASTM C101213 and EN 197-1, in which sulfate resistance is measured through mass loss or expansion. Adapted for Russian conditions. It takes into account the composition of slags and environmental efficiency.

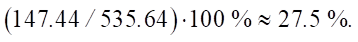

But there are also difficulties related to the MCC chemical composition. The content of MgO (7.67–10.54%) and R2O (0.83–1.52%) in MCC slags does not comply with GOST. A high level of MgO reduces sulfate resistance by 0.2–0.3 c.u. The reason is the formation of Mg (OH)2, which, when expanded, creates internal stresses and provokes cracking. R2O (Na2O + K2O) enhances alkali-silicate corrosion at pH > 12 [22]. The permissible level of R2O in cements with active additives, according to ASTM C61814 and EN 45015, should not exceed 0.6–1.0% in terms of Na2O. In the slags of the studied mixtures, a value of up to 1.52% is fixed, which can lead to instability. Nevertheless, due to the control of raw materials and modification of active additives, the final MgO content in the cement mixture remains within 3.2–4.8%. In particular, EN 197–116 and its versions, for example BS EN 197–5:202117, set a limit value of MgO ≤ 55%, while ASTM C15018 allows values up to 6% for certain types of cements (for example, Type V), provided that a certain strength and stability are ensured (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 The effect of MgO content on the strength and porosity of cement

The graph shows how the MgO content affects the properties of cement. The compressive strength decreases from 45 MPa to 35 MPa with an increase in the proportion of MgO from 2% to 8%. Porosity increases from 8% to 18% with the same MgO range. This confirms the need to control MgO at a level of ≤ 5% to ensure high strength and low porosity.

Scientific publications confirm that the MgO content of more than 5–6% increases the risk of formation of free periclase, which, upon hydration, turns into Mg(OH)2. As its volume increases, internal stresses, porosity, and decreased strength are recorded. Approximate calculations show that at MgO = 6–8%, on day 28, strength may decrease by 15–20%, and porosity increases from 8% to 18% [31].

Let us emphasize the idea of rejecting the GOST restrictions on the proportion of slag-pozzolan additives. According to the standard, this indicator should not exceed 35–40%. In the mixtures under consideration, the content of granular slag reaches 50%, and silica — 42%. This made it possible to obtain a strength of ≈ 44 MPa on the 28th day, which is higher than the requirements of GOST for CEM III/A and even corresponds to CEM I 42.5. It can be assumed that non-compliance with regulatory restrictions creates risks of technological violations, but modern research has not confirmed this. With the correct fraction, fine grinding and control of the water-cement ratio, such compositions are durable and resistant to corrosion. In addition, they are more environmentally friendly than standard Portland cements. Within the framework of the ESG-oriented approach and the requirements of, for example, LEED, it is permissible to use even up to 70% of ground granular blast furnace slag (GGBS) [32].

The main components of blast furnace slag are CaO (30–50%), SiO2 (28–38%), Al2O3 (8–24%), MnO и MgO (1–18%). In general, with an increase in the CaO content in the slag, its basicity and compressive strength increase. MgO and Al2O3 have a positive effect only up to a certain threshold. An increase in MgO to ~10–12% and Al2O3 to ~14% is accompanied by an improvement in strength characteristics. However, exceeding these values may cause the opposite effect. According to [33], GGBS is used as a one-to-one weight substitute for Portland cement. Replacement levels for GGBS range from 30% to 85%. In this respect, GOST 22266–2013 is outdated.

Ecological aspect. Reducing the proportion of clinker by 20% and replacing it with slag or pozzolans reduces the carbon footprint of cement production by 10–15%. CO2 emissions from the production of sulfated cements account for only 9% of the emissions of traditional Portland cement. This is achieved by reducing the proportion of clinker to 5%. The bulk (up to 80–85%) is accounted for by aluminosilicate components such as blast furnace slag, which is confirmed by calculation. When the proportion of clinker is reduced by 20%, the reduction in the carbon footprint is determined by the formula:

(13)

(13)

where Pclinker_original — specific clinker emissions (765.2 kg CO2/t); Rclinker — initial clinker fraction (70% = 0.7);

Psubstitute — specific slag emissions (28 kg CO2/t); Rsubstitute — new slag fraction (20% = 0.2).

Percentage reduction of the carbon footprint:

Let us note the significant level of the calculated reduction of CO2 emissions — 27.5%.

Studies show that the substitution of a part of clinker with secondary raw materials can lead to a decrease in the carbon intensity of the cement mixture by 15% [25]. Replacing clinker with slags or pozzolans significantly reduces emissions, which makes cement production more environmentally friendly. The production of sulfoaluminate cement is characterized by lower CO2 emissions compared to traditional Portland cement. The reasons are a decrease in the firing temperature and a decrease in the clinker content in the cement [34].

To achieve the maximum carbon footprint reduction, it is necessary to use slags with SiO2 > 40% and low CaO content to avoid excessive alkalinity. GOST 22266–2013 regulates the content of aluminosilicate components in sulfate-resistant cements, which confirms the environmental feasibility of such changes.

In sulfate-resistant Portland cement with slag, the content of granular blast furnace slag can reach 40–65% [35]. With a slag content of 80–85%, the CO2 volume will be less than 10% of the emissions of standard Portland cement (0.8–0.9 kg of CO2 per 1 kg of material), which is consistent with calculations [36].

Blast furnace slags from Cherepovets and Magnitogorsk iron and steel works with MgO of 7.67–10.54% require processing to comply with GOST. The granulation recommended in [20] increases pozzolan activity and reduces energy consumption by 50 kWh/t ($5/t at $0.1 /kWh in 2025). Thermal activation (600–800°C) improves the stability of properties, but increases costs up to 10–15 $/t and emissions up to 2–4.5 kg/t of CO2 (0.02–0.03 kg of CO2/kWh) [25]. Logistical costs (500–1000 km delivery) add 5–10 $/t [25] and 25–100 kg of CO2/t [20]. But localization, the use of local slags minimizes these costs by 80–90%. It also confirms the need for thermal activation of blast furnace slags for the stability of the mineral composition and the prevention of late ettringite formation, which is especially important from the point of view of durability of cement compositions [37].

Conclusion. Thus, replacing 20–50% of clinker with slag reduces the CO2 level by 27.5%, to 388.2 kg of CO2/t (ΔCO2 = 147.44 kg/t). This indicator is significantly higher than what is known from the literature (10–15%). This result ensures low slag emissions (28 kg CO2/t in comparison with 800 kg/t clinker), but requires MgO control (≤5%) to prevent porosity. The proposed model overcomes the limitation of GOST 22266–2013 (C3A ≤7%), integrates SiO2 and CO2, and thus ensures compliance with ESG approaches to the production and operation of cement products.

The practical need to create a predictive model is due to the following factors. Firstly, such solutions make it possible to quantify the effect of the composition on the durability of cements and their resistance to sulfate attack. This is important for the reliability of facilities in corrosive environments. Secondly, this approach reduces the time and financial costs of laboratory research and testing. Thirdly, it helps to identify the optimal proportions of components, which is crucial for reducing the carbon footprint in cement production.

The regression model described in the article showed accuracy in predicting the sulfate resistance of cements depending on the SiO2 content (21–44%). This was confirmed by the analysis of variance. The author focuses on the SiO2 content as a key factor for increasing sulfate resistance. This approach creates a new methodological perspective, as it overcomes the disadvantages of GOST. The standard focuses on С3А and basicity and does not explicitly single out the SiO2 level as a significant parameter of the processes under consideration.

It was found that an increase in the proportion of SiO2 from 22.15% to 42% increased sulfate resistance from 8.04 to 9.62 c.u. A decrease in the content of C3A to ≤ 8% and SO3 to ≤ 3 % ensured compliance with GOST 22266–2013 for sulfate-resistant cements (CEM III/A SR). Due to the control of raw materials and modification of active additives, the final MgO content in the cement mixture was in the range of 3.2–4.8%.

The paper presents quantitative calculations of CO2 reduction with a change in composition, whereas GOST 22266–2013 and other standards describe strength and technological parameters without taking into account environmental aspects. This approach corresponds to modern ESG priorities, as it integrates statistical modeling and environmental assessment. Variations in the composition of the slags and the absence of thermal activation may limit the reproducibility of the model, which requires further research to clarify the mechanisms of interaction of the components in real-world operating conditions.

1. How to Protect Materials from the Climate. Rare Earths. 2018. (In Russ.) URL: https://rareearth.ru/ru/pub/20180831/04072.html (accessed: 03.09.2025).

2. Regnum IA. The Economies of the Leading Countries are Losing Trillions Due to Corrosion, the Scientist Said. (In Russ.) URL: https://regnum.ru/news/2473576?ysclid=mf9qsfdnef959278558 (accessed: 03.09.2025).

3. Hays G.F. Corrosion Costs and the Future. URL: https://corrosion.org/Corrosion+Resources/Publications.html (accessed: 03.09.2025).

4. El-Feky MS, Badawy AH, Mayhoub OA, Kohail M. Enhancing Sulfate Attack Resistance of Cement Mortar through Innovative Nano-Silica and Nano-Cellulose Incorporation: A Comprehensive Study. Asian Journal of Civil Engineering. 2024; Apr. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-4248270/v1. Preprint. URL: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-4248270/v1 (accessed: 03.09.2025). Preprint. The work is licensed in accordance with the international ““License” With the indication of authorship”” — Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (editor's note).

5. GOST 4013–2019. Gypsum and Gypsum-Anhydrite Rock for the Manufacture of Binders. Specifications. Electronic Fund of Legal and Regulatory and Technical Documents. (In Russ.) URL: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/1200169320 (accessed: 03.09.2025).

6. GOST 310.1.76. Cements. Test Methods. General. Internet and Law. (In Russ.) URL: https://internet-law.ru/gosts/gost/34404/?ysclid=m9hv0dql9976146066 (accessed: 03.09.2025).

7. GOST 310.4–81. Cements. Methods of Tests of Bending and Compression Strengths. Internet and Law. (In Russ.) URL: https://internet-law.ru/gosts/gost/13713/ (accessed: 03.09.2025).

8. TU 21–26–13–90. Stressing Cement. Russian Institute of Standardization. (In Russ.) URL: https://nd.gostinfo.ru/document/3203787.aspx (accessed: 03.09.2025). Replaced by GOST R 56727–2015. Self-Stressing Cements. Specifications.

9. GOST 31108–2020. Common Cements. Specifications. Internet and Law. (In Russ.) URL: https://internet-law.ru/gosts/gost/73873/?ysclid=m9iwx3cpwg983001164 (accessed: 02.09.2025).

10. GOST 22266–2013. Sulphate-Resistant Cements. Specifications. Electronic Fund of Legal and Regulatory and Technical Documents. (In Russ.) URL: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/1200111313 (accessed: 03.09.2025).

11. Id.

12. CEM I SR — sulfate-resistant Portland cement; CEM II/A SR and CEM II/B SR — sulfate-resistant Portland cements with mineral additives; CEM III/A SR — sulfate-resistant Portland cement with slag.

13. ASTM C1012 — Standard Test Method for Length Change of Hydraulic-Cement Mortars Exposed to a Sulfate Solution URL: https://store.astm.org/c1012_c1012m-18b.html (accessed: 05.10.2025).

14. ASTM C618-2017. Standard Specification for Coal Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete. URL: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/556607883 (accessed: 27.09.2025).

15. MSZ EN 450-1-2013. Fly Ash for Concrete. Part 1: Definition, Specifications and Conformity Criteria. URL: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/554094968 (accessed: 27.09.2025).

16. EN 197–1:2011. Cement — Part 1: Composition, Specifications and Conformity Criteria for Common Cements. Brussels: CEN; 2011. URL: http://www.puntofocal.gob.ar/notific_otros_miembros/mwi40_t.pdf (accessed: 03.09.2025).

17. BS EN 197–5:2021. Cement — Portland-composite cement CEM II/C-M and Composite Cement CEM VI. British Standards Institution (BSI). URL: https://knowledge.bsigroup.com/products/cement-portland-composite-cement-cem-ii-c-m-and-composite-cement-cem-vi (accessed: 03.09.2025).

18. ASTM C150/C150M–24. Standard Specification for Portland Cement. West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International; 2024. URL: https://doi.org/10.1520/C0150_C0150M-24 (accessed: 03.09.2025).

References

1. Barbhuiya S, Kanavaris F, Das BB, Idrees M. Decarbonising Cement and Concrete Production: Strategies, Challenges and Pathways for Sustainable Development. Journal of Building Engineering. 2024;86:108861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.108861

2. Ovchinnikov KN. Carbon Footprint of Cement Industry. Influence Factors, Trends and Points of Improvement. Nedropol'zovanie XXI vek. 2022;4(96):127–137. (In Russ.) URL: https://nedra21.ru/upload/iblock/-bb8/mbm3y200f3dkf194s8121y5uc0xm6l69/127_137_K.N.-Ovchinnikov.pdf (accessed: 03.09.2025).

3. Jingjun Li, Shichao Wu, Yuxuan Shi, Yongbo Huang, Ying Tian, Duinkherjav Yagaanbuyant. Effects of Nano-SiO2 on Sulfate Attack Resistance of Multi-Solid Waste-Based Alkali-Activated Mortar. Case Studies in Construction Materials. 2025;22:e04227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2025.e04227

4. Moslemi AM, Khosravi A, Izadinia M, Heydari M. Application of Nano Silica in Concrete for Enhanced Resistance against Sulfate Attack. Advanced Materials Research. 2013;829:874–878. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/amr.829.874

5. Xinzhe Li, Ganyou Jiang, Naishuang Wang, Yisong Wei, Zheng Chen, Jing Li, et al. Effect of Chlorides on the Deterioration of Mechanical Properties and Microstructural Evolution of Cement-Based Materials Subjected to Sulphate Attack. Case Studies in Construction Materials. 2025;22:e04235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2025.e04235

6. Dvorkin L, Zhitkovsky V, Marchuk V, Makarenko R. High-Strength Concrete Using Ash and Slag Cements. Materials Proceedings. 2023;13(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2023013016

7. Scrivener K, Snellings R, Lothenbach B. (eds). A Practical Guide to Microstructural Analysis of Cementitious Materials. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2016. 560 p. https://doi.org/10.1201/b19074

8. Junliang Zhao, Kangning Song, Zhongkun Wang, Dongyan Wu. Effect of Nano-SiO2/Steel Fiber on the Mechanical Properties and Sulfate Resistance of High-Volume Fly Ash Cement Materials. Construction and Building Materials. 2023;409:133737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133737

9. Bo Pang, Yanquan Yang, Yunpeng Cui. Corrosion Resistance Behavior of MgO-SiO2-KH2PO4 Cement under Sulfate Environments. Ceramics International. 2024;51(6):8156–8167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.12.251

10. Imbabi MS, Carrigan C, McKenna S. Trends and Developments in Green Cement and Concrete Technology. International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment. 2012;1(2):194–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsbe.2013.05.001

11. Snellings R, Suraneni P, Skibsted J. Future and Emerging Supplementary Cementitious Materials. Cement and Concrete Research. 2023;171:107199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2023.107199

12. Mehta PK, Monteiro PJM. Concrete: Microstructure, Properties, and Materials. Columbus: McGraw-Hill Education; 2014. 675 p. URL: https://www.amazon.com/Concrete-Microstructure-Properties-Kumar-Monteiro/dp/X?asin=0071797874&revisionId=&format=4&depth=1 (accessed: 03.09.2025).

13. Shvedova MA, Artamonova OV, Rakityanskaya AYu. Nano- and Micro-Modification of Cement Stone with Complex Additives Based on SiO2. Bulletin of Civil Engineers. 2021;6(89):105–114. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.23968/1999-5571-2021-18-6-105-114

14. Akieva EA. Forecasting the Grade Strength of Cement Systems Based on the Results of Short-Term Tests and Mineralogical Composition. Cand.Sci. (Engineering) diss. Belgorod: BSTU; 2006. 150 p. (In Russ.) URL: https://new-disser.ru/_avtoreferats/01003301328.pdf (accessed: 03.09.2025).

15. Kharitonov AM. Principles of Forecasting the Properties of Cement Composite Materials Based on Structural Simulation Modeling. Proceeding of Petersburg Transport University. 2009;1:141–152. (In Russ.)

16. Benson SM, Orr JrFM. Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage. MRS Bulletin. 2008;33(4):303–305. https://doi.org/10.1557/mrs2008.63

17. Laissy MY, Rashed HF. 3D Printing Technology for Construction: A Structural Shift in Building Infrastructure. In: Proceedings of the ICSDI 2024. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering. Mansour Y, Subramaniam U, Mustaffa Z, Abdelhadi A, Al-Atroush M, Abowardah E. (eds). Singapore: Springer; 2025. Vol. 558. P. 135–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-8345-8_17

18. Sharma M, Bishnoi S, Martirena F, Scrivener K. Limestone Calcined Clay Cement and Concrete: A State-of-the-Art Review. Cement and Concrete Research. 2021;149:106564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2021.106564

19. Ishrat Hameed Alvi, Qi Li, Yunlu Hou, Chikezie Chimere Onyekwena, Min Zhang, Abdul Ghaffar. A Critical Review of Cement Composites Containing Recycled Aggregates with Graphene Oxide Nanomaterials. Journal of Building Engineering. 2023;69:105989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.105989

20. Smirnova OM, Kazanskaya LF. Industrial Waste Products Based Concrete: Environmental Impact Assessment. Russian Journal of Transport Engineering. 2022;2(9):1–22. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.15862/05SATS222

21. Cuesta A, Ayuela А, Aranda MAG. Belite Cements and Their Activation. Cement and Concrete Research. 2021;140:106319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2020.106319

22. Elahi MA, Shearer CR, Reza ANR, Saha AK, Khan NN, Hossain M, et al. Improving the Sulfate Attack Resistance of Concrete by Using Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs): A Review. Construction and Building Materials. 2021;281:122628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122628

23. Pospelova E, Chernositova E, Lazarev EV. Statistical Quality Analysis of the Russian Cement. Bulletin of Belgorod State Technological University Named after. V.G. Shukhov. 2017;7:180–186. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.12737/article_5940f01b05bef8.10658659

24. Andreev VV, Smirnova EE. Cement Containing Portland Cement Clinker, Calcium Hydrate and Sulfate Component. RF Patent, No 2079458 C1. 1997. 6 p. (In Russ.) URL: https://patents.s3.yandex.net/RU2079458C1_19970520.pdf (accessed: 03.09.2025).

25. Smirnova EE. Assessment and Prediction of the Environmental Performance of Multi-Component Cements Using Statistical Analysis. Safety of Technogenic and Natural Systems. 2025;9(2):87–101. https://doi.org/10.23947/2541-9129-2025-9-2-87-101

26. Skobelev DO, Potapova EN, Mikhailidi DKh, Rudomazin VV. Blast Furnace Slag as a Construction Material for Arctic Sustainable Development. The North and the Market: Forming the Economic Order. 2024;2(84):88–99. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.37614/2220-802X.2.2024.84.007

27. Bastrygina SV, Konokhov RV. Influence of Silica-Containing Additives on Strength Properties of Lightweight Concrete on Porous Aggregate. Transactions of the Kola Science Centre of RAS. Natural Sciences and Humanities Series. 2022;1(2):58–66. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.37614/2949-1182.2022.1.2.007

28. Potapov V, Kashutin A, Serdan A, Shalayev K, Gorev D. Nanosilica: Increase of Concrete Strength. Nanoindustry. 2013;3(41):40–49. (In Russ.) URL: https://www.nanoindustry.su/journal/article/3682?ysclid=mge0xusa4q171412223 (accessed: 03.09.2025).

29. Zehra Funda Akbulut, Soner Guler. Enhancing the Resilience of Cement Mortar: Investigating Nano-SiO2 Size and Hybrid Fiber Effects on Sulfuric Acid Resistance. Journal of Building Engineering. 2024;98:111187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.111187

30. Ovchinnikova EV. Investigation of the Effect of the Type of Magnesia Flux on the Phase Composition of the Agglomerate in Order to Increase Its Strength Characteristics. Cand.Sci. (Engineering) diss. Moscow: MISiS; 2018. 148 p. (In Russ.) URL: https://rusneb.ru/catalog/000199_000009_010009494/?ysclid=mge0tqa0uj357076568 (accessed: 03.09.2025).

31. Vipulanandan C, Demircan E. Designing and Characterizing the LEED Concrete for Drilled Shaft Applications. GeoFlorida 2009. Contemporary Topics in Deep Foundations, ASCE. Iskander M, Laefer DF, Hussein MH. (eds.). Orlando: ASCE; 2009. P. 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1061/41021(335)7

32. Snellings R, Mertens G, Elsen J. Supplementary Cementitious Materials. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 2012;74(1):211–278. https://doi.org/10.2138/rmg.2012.74.6

33. Askarian M, Fakhretaha Aval S, Joshaghani A. A Comprehensive Experimental Study on the Performance of Pumice Powder in Self-Compacting Concrete (SCC). Journal of Sustainable Cement-Based Materials. 2019;7(6):340–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650373.2018.1511486

34. Min Hein Htet, Potapova EN, Burlov IY. Kinetics of Mineral Formation in the Synthesis of Sulfoaluminate Clinker. Uspekhi v Khimii i Khimicheskoi Tekhnologii. 2022;36(3):106–108. (In Russ.) URL: https://www.muctr.ru/upload/iblock/7ee/zb2awjbwjx0eaaorpzycxwfskfquwwmu.pdf (accessed: 03.09.2025).

35. Falaleeva NA, Falaleev AG. Enbironmental Issues and Perspectives of New Raw Materials in Production of Slag Portland Cement. Vestnik MGSU. 2011;3(2):52–58. (In Russ.) URL: https://www.litres.ru/ (accessed: 03.09.2025).

36. Vanderley MJ. On the Sustainability of the Concrete. Industry and Environment. 2003;26(2):1–7. URL: https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/7615945/on-the-sustainability-of-the-concrete-vanderley-moacyr-john-usp (accessed: 03.09.2025).

37. Thomas M, Folliard KJ, Drimalas T, Ramlochan T. Diagnosing Delayed Ettringite Formation in Concrete Structures. Cement and Concrete Research. 2008;38(6):841–847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2008.01.003

About the Author

E. E. SmirnovaРоссия

Elena E. Smirnova, Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Associate Professor of the Department of Industrial Ecology

ElibraryID: 438628

14, Professora Popova St., lit. A, St. Petersburg, 197376

Predictive models for cement composition, in terms of sulfate resistance and ecological impact, have been developed. These models show the decisive effect of silicon dioxide on the sulfate resistance of cement. A method for selecting additives based on silicon dioxide content and strength has been proposed. It has also been found that using granulated slag in cement reduces the carbon footprint by a quarter. This model allows for choosing the composition of concrete based on economic and environmental criteria, and the results can be used to ration and design durable structures.

Review

For citations:

Smirnova E.E. Statistical Modeling of Sulfate Resistance and Carbon Footprint for Optimization of Multi-Component Cements. Safety of Technogenic and Natural Systems. 2025;9(4):263-283. https://doi.org/10.23947/2541-9129-2025-9-4-263-283. EDN: BBSFOR

JATS XML